Clare Vergobbi

Snow, ice and negative temperatures: winter has come to the Sawtooths, and the 2023 salmon runs are a wrap. We’ve received final numbers for sockeye and chinook returns to the Sawtooth Valley from Idaho Fish and Game. It was an impressive year for chinook, with 3,001 adults returning to spawn in the Sawtooth Valley. Sockeye numbers were far lower, at only 174 adults.

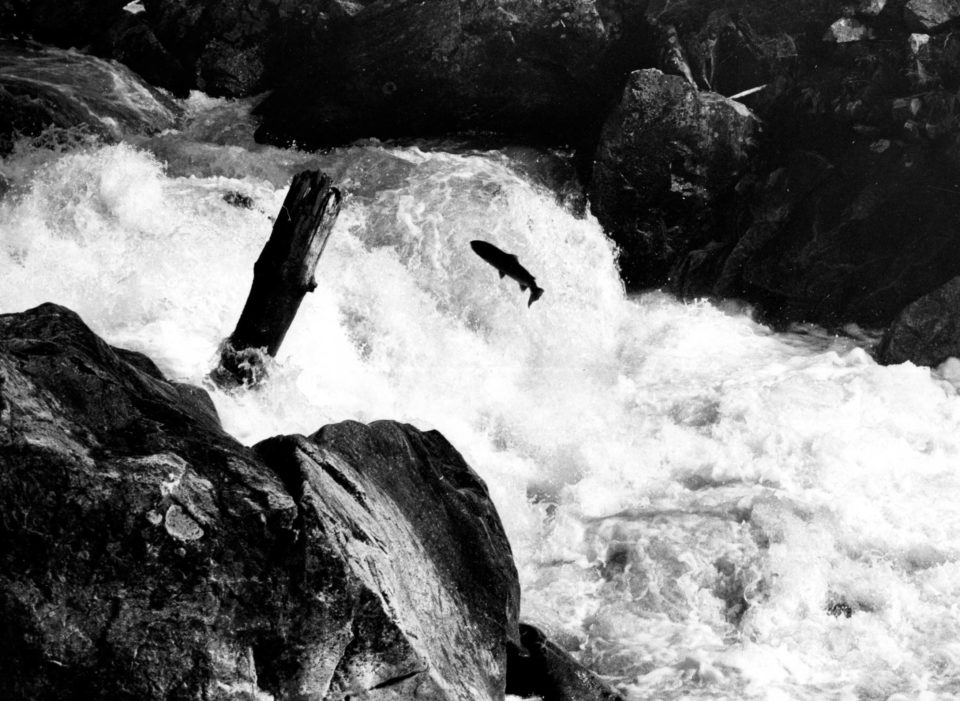

Historically, chinook populations in the Snake River Basin hovered around 1 to 1.5 million. Sockeye populations in the Sawtooth Basin were around 50,000. Early white settlers in the region told stories of throwing stones in the river during spawning season to scatter the fish so horses could cross without crushing or slipping on them, and sport salmon and steelhead fishing was one of the early tourism draws to Sawtooth country. But both Snake River sockeye and chinook numbers have decreased dramatically over the fifty years due to erratic ocean temperatures, changing snowmelt patterns, and other impacts of climate change and increasing numbers of dams and stillwater reservoirs on the Snake and Columbia rivers. Both species are hovering near extinction and are listed under the Endangered Species Act, but chinook returns are regularly exponentially higher than sockeye returns. Both fish are anadromous, meaning they travel from their spawning waters high in the Idaho mountains, all the way down the Snake and Columbia rivers to the Pacific Ocean. Both make the journey during high water in spring, and return during the summer and early autumn. So: why such a difference in numbers?

There are a few reasons. First, chinook return earlier in the summer, from late June to late August. They usually pass by the eight dams and reservoirs on the Snake and the Columbia before the hottest days of the summer, when water temperatures rise and water levels are at their lowest. They are also a hardier species than sockeye, able to withstand warmer temperatures up to a point. A Canadian study quantified their thermal tolerance and ability to genetically adapt to water temperatures around 75ºF while sockeye mortality rises when temperatures increase above around 60ºF. Chinook also have a larger general population in the Columbia Basin than sockeye do, which is important for the maintenance of genetic diversity and the ability to genetically adapt to changing conditions. Sockeye return between August and early October, meaning they complete most of their journey during the warmest weather and at the lowest river flow. This year, water temperatures at Ice Harbor and Lower Monumental dams both reached 70ºF in mid-July, above the harm threshold of 68ºF for all migrating salmon and steelhead and in the midst of the sockeye migration.

Springtime conditions also play a role. Young fish (called smolts) need high water to flush them downstream to the ocean. Smolts don’t swim downstream as much as they are washed downstream tail-first. High waters wash them safely over the top of spillways, but if the water is too low they often go through turbines or are trapped in the reservoirs instead. Chinook tend to stay in the ocean for 2-5 years while Sockeye return after 2-3 years, so the adult salmon returning likely did not all migrate to the ocean in the same year and had varying mortality rates in their downstream migration.

The migrations of Snake River Sockeye and Chinook are some of the longest anadromous fish migrations in the world. These amazing animals travel over 900 miles and around 7000 vertical feet to reach their spawning grounds in the Sawtooth Valley. Conservation efforts to prevent the extinction of these species are critical to maintaining the biological diversity of the SNRA. If you’re interested in learning more about salmon conservation, visit https://idfg.idaho.gov/conservation/sockeye, https://www.idahorivers.org/salmon, or https://www.idahoconservation.org/our-work/salmon-and-steelhead/.

Clare Vergobbi is SIHA’s summer programs coordinator. They love exploring Sawtooth country, baking bread, and teaching people about Idaho’s incredible salmon and steelhead!