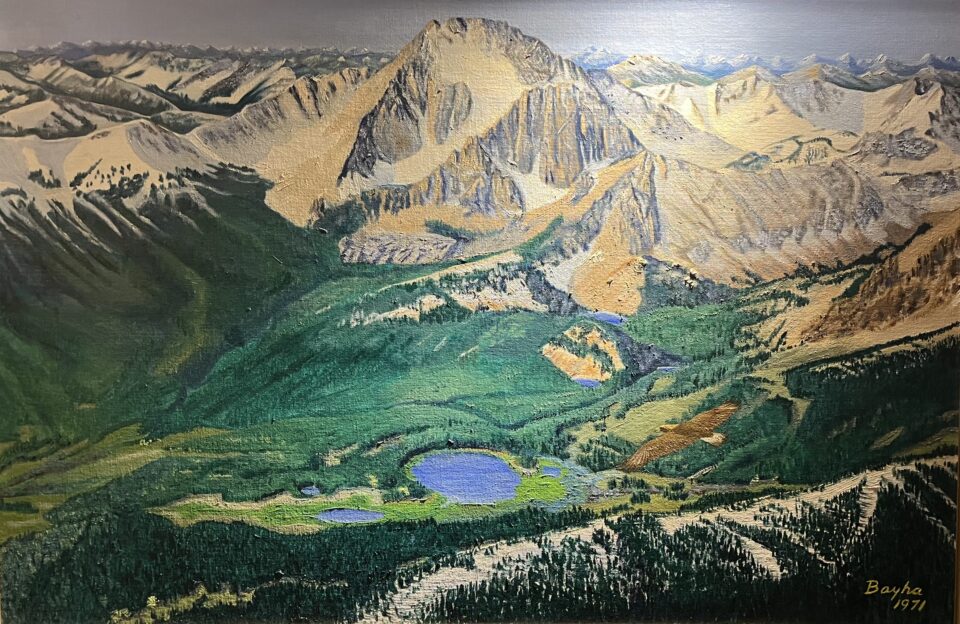

The White Cloud Mountain skyline. Photo Credit: Bureau of Land Management

Spanning nearly 91,000 acres, the Cecil D. Andrus White Clouds Wilderness is something of a hidden gem on the Sawtooth National Recreation Area. The jagged and imposing peaks of the White Cloud mountains tower above a landscape patchworked by green groves of pine, crystal clear creeks, and pristine alpine lakes—a landscape that was once nearly destroyed by mining.

Let’s rewind for a moment, back to the year 1967. ASARCO, one of the largest mining companies in the world, decided to investigate a report sent out two years previously from the U.S. Geological Survey. This report published the results of an even earlier survey from 1943 in which evidence of molybdenum was noted to be found around the base of Castle Peak, the highest peak in the White Clouds. A claim had been filed on the land also in 1943, but ASARCO contacted the owner of the claim and purchased the rights from him. The following May, helicopters, a drilling rig, and a crew prepared to operate on shifts for 20 hours a day were dispatched into the backcountry to begin preliminary surveys of mineral deposits.

At this point in time, mining on public lands was, if not explicitly allowed, faced with very few regulations and limitations. While a secret to the public, ASARCO’s initial surveys of the land were known to the Forest Service and kept under wraps—the Forest Service did not want to risk the removal of that land from under their management. As drilling continued through the summer of 1968 to determine if the deposits would be profitable enough to warrant the construction of a remote mine, reports of the ongoing survey activity slowly began to be leaked to the public from hikers in the White Clouds.

The nature of these operations was already causing significant damage to the ecosystem as refuse was dumped into alpine lakes and streams. Despite complaints to the Forest Service to stop the proceedings, nothing was done.

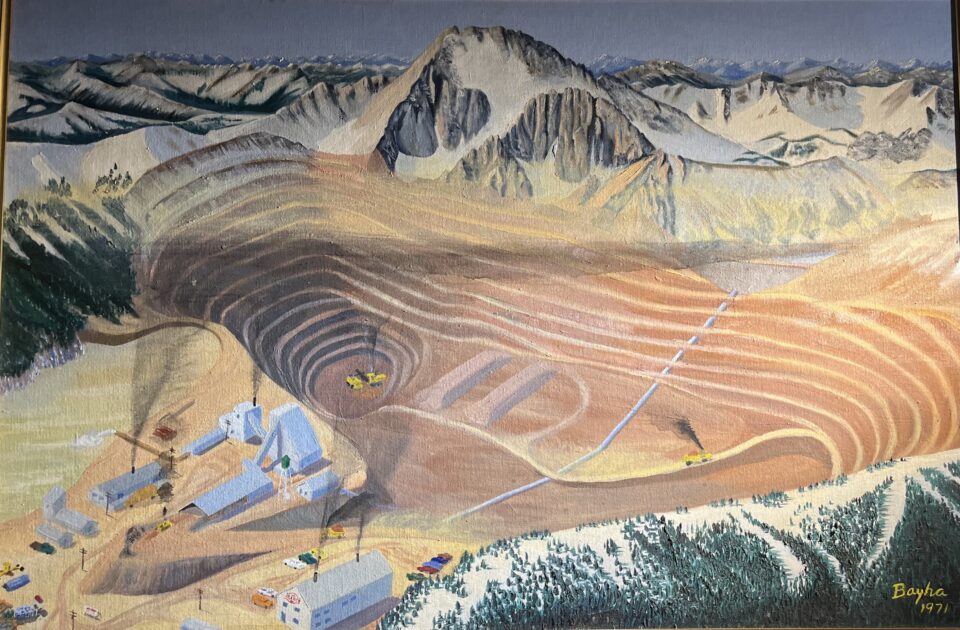

Over the next few years, the question became not whether or not a mine would be constructed, but what kind of mine would be best suited to extract the rich molybdenum deposits under Castle Peak. An open-pit mine was proposed, which would cause catastrophic damage to the landscape, and the necessary service roads and construction work would further ravage the surrounding land. Intense debate began to flare up around the issue, as conservationists, politicians, and mining industry leaders all took heated stances on either side of the mine issue.

It was at this point that Cecil Andrus entered the scene—a figure who would leave an impact on the land so great that he would become the namesake of the future White Clouds Wilderness area. Originally from Oregon, Andrus moved to Idaho after serving in the Korean War, ran for office in 1960, and was elected to the Idaho State Senate. After four consecutive terms, he decided to run for governor on the Democratic ticket, focusing his campaign on issues of education and environmentalism.

Cecil did not become actively involved in the fight for the White Clouds until February of 1970. At this point, he sponsored a bill that would ban dredging along wild rivers and introduced legislation to regulate surface mining that would require proof of plans for revegetation and minimizing environmental impacts. He claimed himself to be trying to find the middle way between the two vehemently opposed sides, attempting to respond to the complaints of mining companies about significant industry impacts while reaffirming that the threat to the White Clouds was his primary concern.

Top painting by artist and activist Kieth Bayha of the pristine conditions of Castle Peak and the surrounding White Clouds. Bottom painting he portrays the likely outcome of an open pit mine, based on images from another such mine in Colorado. Photo Credit: SIHA staff

The dispute had reached beyond the narrow confines of whether or not to preserve a pretty landscape, and now became a question of how public lands should be managed. Was there value to the land beyond economic opportunity? How should public land be used to best benefit the people it was designated for? And most importantly: Was it possible for a politician to run and gain office on an environmentalist ticket?

To be continued next week!

For further reading on Cecil Andrus and the fight for the White Clouds, see attached links:

Short bio of Governor Andrus – National Governors Association

Recommended Books:

To the White Clouds: Idaho’s Conservation Saga, by J.M. Neil

Defending Idaho’s Natural Heritage, by Ken Robison

Azelie Wood is a historic specialist, working at the Stanley Museum. Though she is a California native, she has already fallen in love with the Sawtooth Mountains, and is excited to explore them this summer. In her free time, she enjoys hiking and reading.